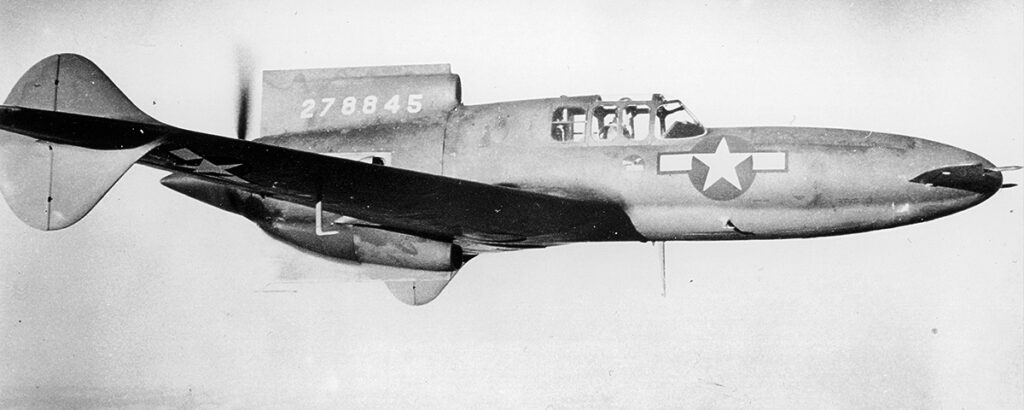

The Curtiss-Wright XP-55 Ascender was probably one of the most distinct and unusual prototype aircraft to take to the skies. Designed in response to a United States military specification in 1939, the XP-55 featured all manner of experimental design features and was built in a canard configuration.

Origins

The XP-55 Ascender originated from a specification issued by the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) in November 1939 which was known as specification R-40 C. The specification called for the design of a new fighter and interceptor aircraft that featured improved speed, pilot visibility and fighting abilities over existing fighter aircraft at the time.

Most importantly, specification R-40 C granted freedom to designers to explore experimental ideas and move away from conventional designs on the condition that the new aircraft would be easy and cheap to maintain.

Around fifty design proposals were sent to the USAAC but most were declined. By 1940, the USAAC had narrowed the competition down to four contending designs from Curtiss-Wright, Northrop, Vultee and Bell.

Read More Vultee XP-54: A Stunning Pusher Plane that Failed to Impress

Curtiss-Wright’s design was perhaps the most unusual and distinctive of the four.

Development

The initial contract called for a powered wind tunnel model to allow for research and data gathering before a flying prototype was produced.

Curtiss-Wright began the project under chief designer Donovan Berlin and was given the designated name CW-24 to start with.

The CW-24 design followed the format of a swept-wing “pusher” aircraft with a canard configuration featuring a small tail at the front of the fuselage with elevators. The wings were also low-mounted, sweptback and equipped with ailerons and flaps on the trailing edge. The wing elevators were located at the front of the nosecone. A retractable tricycle undercarriage was also proposed for the design and it was the first time such an undercarriage was fitted to a Curtiss-Wright fighter.

Curtiss-Wright also wanted to use the new but, at the time, untested Pratt & Whitney X-1800-A3G liquid-cooled engine. The design called for the engine to be mounted behind the cockpit where it would drive a pusher propeller.

Wind tunnel tests commenced with the experimental design, but the USAAC were not wholly satisfied with the results delivered by the research team. However, the Curtiss-Wright team persevered and continued to work on the design by themselves.

Read More Ilyushin IL-76 Candid – Jack of all Trades

An updated prototype idea was named the CW-24B by the company and the engine was switched so the plane would now be driven by a 275 horsepower Menasco C68-5 engine for testing, which lowered the top speed to around 180 miles per hour. The new design had a welded steel tube fuselage covered in a fabric lining while the wings were made from wood. The undercarriage was also changed from retractable to fixed.

In 1941, a finished airframe of the new design was transported to the army aircraft testing centre at Muroc Dry Lake (now know as Edwards Air Force Base) for further testing and preparation for its maiden flight.

The CW-24B model completed its maiden flight in December 1941. Initial test flights showed that the CW-24B was a viable concept idea with the potential to be developed into an effective fighter aircraft. However, test pilots found the aircraft to also have stability issues and complained of lack of directional control in some situations. Curtiss-Wright responded by modifying the CW-24B’s winglets and enlarging the wings which was found to produce better results. Further updates were made by adding vertical fins to both the top and the bottom of the engine cowling. Test pilots noted that this also improved the handling considerably and made the aircraft easier to fly.

Several further test flights were made at Murcoc between December 1941 and May 1942 before it was shipped to Langley Field, Virginia for a final round of testing.

In July 1942, the USAAC’s successor the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) issued a contract to Curtiss-Wright for three new models of the CW-24B and the aircraft’s name was changed to the XP-55 “Ascender,” initially based on a joke about the plane made by a Curtiss-Wright employee. It was also jokingly known as the “Ass-ender”, in reference to its backwards design.

Curtiss-Wright still wanted to fit the experimental Pratt & Whitney engine to their design, but this still proved unavailable before Pratt & Whitney decided to cancel the project altogether. Instead, an existing Allison V-1710 liquid cooled engine was fitted to the XP-55 which proved to be just as reliable and crucially more easy to obtain.

The proposed weapons system for the aircraft was to be two 20-mm cannons and two 0.50-inch machine guns mounted on the wings and at the front. This would later be changed to just four machine guns.

The Ascender takes flight

The first full XP-55 unit was built in July 1943 and essentially followed most of the CW-24B’s design. It completed its maiden flight on the 19th of June 1943 at Scott Field airfield near the Curtiss-Wright factory in St Louis.

One remarkable new safety feature for the plane was devised by engineer W. Jerome Peterson which was a propeller jettison lever inside the cockpit. Peterson noted the plane’s rear-propeller design could pose a potential danger to pilots should they need to bail out of the plane, and he sought to mitigate any risk of the pilot hitting the propeller.

Read More N1 Rocket – The Most Powerful Space Rocket Ever Built

The chief test pilot was Harvey Grey. His reports from the first round of flight testing concluded that the takeoff run was too long compared to other aircraft. To address the problem, the XP-55’s nose elevator was increased in area and the aileron up trim was interconnected with the flaps so that it would function while the flaps were lowered.

In November 1943, Grey was tasked with putting the XP-55 through a series of emergency stall tests at Scott Field. The tests began as routine before Grey suddenly lost control of the aircraft in the air. Without warning, the plane rolled onto its back and began falling into an inverted, uncontrolled spin towards the ground. Grey tried recovering the aircraft as it fell for a stomach churning 16,000 feet before recovery was deemed impossible. Gray was able to exit the cockpit and parachute to safety but the prototype was completely destroyed as it crashed into the ground.

Unfortunately, it was too late in the production process to make any significant changes to the second XP-55 unit based on preliminary investigation reports into the crash. The second XP-55 more or less followed the same design layout as the first unit, with the only significant change being a larger nose elevator. The second unit completed its maiden test flight in January 1944, but following the crash of the first model, all test future XP-55 flights were restricted and closely regulated by military authorities until the third and improved XP-55 model had completed its testing process.

The third completed XP-55 airframe made its first flight in April 1944 at Scott Field. This time, the design incorporated changes based on follow up reports after the crash of the first unit. Research and tests found that stall prevention and management could be improved by adding a four-foot winglet extension and allowing for wider, more flexible nose elevator travel.

However, perhaps ironically the initial test flight found that the new elevator modifications meant that the pilot could take off with a dramatically increased angle of attack but as a result the aircraft could potentially stall during takeoff. Furthermore, there was criticism from pilots over the lack of stall warning in the aircraft.

Further modifications were made, including fitting a stall warning system, and the third XP-55 managed to pass subsequent stall tests and was deemed fit for flight.

Fate

Although Curtiss-Wright had managed to rectify some of the issues experienced by earlier XP-55 models, the overall performance was still deemed unimpressive and even inferior compared to other, more conventionally designed fighter planes by test pilots in their reports.

Read More Vought V-173 – America’s Flying Pancake

By 1944, the Nazi regime had also launched research into and successfully developed early models of jet fighter planes. Allied forces were also catching up, with Britain having already produced and tested the design for the Gloster Meteor fighter jet in 1943.

Knowing that jet engine technology pointed to the future direction of newer fighter aircraft, Curtiss-Wright began to wind down the XP-55 project by late 1944. No further development was made on the aircraft and it never progressed into mass production.

The fate of the XP-55 was perhaps sealed in 1945 when the third prototype was performing at an air show at Wright Field, Ohio where it crashed and killed both the pilot and four spectators on the ground.

Legacy

While the XP-55 was unsuccessful in reaching the mass production stage and went through a torrid design process, it nonetheless remains an intriguing example of an experimental aircraft when design freedom was allowed.

One XP-55 airframe survived and was initially kept by Curtiss-Wright. It was later transferred to Warner Robins Field in Georgia in May 1945 where it sat in storage. It was later taken to Freeman Field, Indiana to await shipment to the National Air Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington where it was intended for display.

For a period, only the XP-55’s fuselage was put on public display at the Paul Garber facility for aircraft rescue and restoration in Maryland. In December of 2001, the surviving XP-55 was transferred to the Kalamazoo Aviation History Museum for a full restoration back to its original specification.

Read More Consolidated B-24 Liberator – Better than the B-17?

The restoration process was finished in 2007 and the plane is now on display at the Kalamazoo Airzoo.

Specifications

- Capacity: 1

- Length: 29 ft 7 in (9 m)

- Wingspan: 44 feet (13 m)

- Height: 10 ft 3 (3.1 m)

- Empty weight: 6,355 lb (2,880 kg)

- Gross weight: 7,940 (3,600 kg)

- Powerplant: Allison V-1710-95 V12 petrol, 1,275 hp

- Maximum speed: 377 mph (606 km/h)

- Range: 1,440 miles maximum

- Service ceiling: 34,600 feet