With only two units produced, Bell X-5 remains one of the most important aircraft in post-WWII history. This plane played a critical role in testing the sweep angle changes of a plane’s wings while flying.

As a pioneer of sweep angle changes, this plane helped the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which was the predecessor of NASA, to research and analyze the advantages of changing the sweep angle of aircraft while in flight. The results would set a new milestone in the history of aircraft.

Contents

Swing Wing

A plane taking off with extended wings would require a smaller takeoff speed and a shorter runway to takeoff compared to a plane with swept-back wings. However, once in the air, the plane would increase the sweep angle which resulted in increased speed and reduced drag for the aircraft.

Read More: MiG-21 Fishbed – The AK-47 of Combat Aircraft

This plane’s unique ability to sweep back its wings at different angles (up to 60 degrees) helped draw plenty of analytic data for NACA and USAF (United States Army Air Force) and led to improvements in the development of planes in the period after the 60s.

Some of the aircraft developed that followed similar principles in variable sweeping wings were; General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark, Gruman F-14 Tomcat, Tupolev Tu-22M Blinder and the Tupolev Tu-160 Blackjack.

Development of the X-5

The basis for the development of this aircraft came from the German-built Messerschmitt P.1101 aircraft. The plane was still in an experimental phase when it was captured by the US troops on 29 April 1945 in Oberammergau, Germany.

Nevertheless, the battle to find Nazi Germany’s innovative technology between Soviets and US troops was fierce. US intelligence troops would question the designer behind the Messerschmitt AG, Woldemar Voigt.

Despite the genius work, the intelligence officers were given the impression that the aircraft would be hardly able to fly.

That is why they pulled it out of the hanger only for display. The aircraft would catch the eyes of Robert Woods, who was a civilian member of the Army’s Intelligence and a Bell Aircraft employee. He saw the potential of the aircraft and requested it to be shipped to the US.

Despite numerous damages sustained in the process of retrieval, and staying for 2 years at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, the aircraft was taken for examination by Bell Aircraft and its head of the design team, Robert Wood.

The P.1101 aircraft was in no condition to fly by that time, however, the design which allowed the aircraft to sweep angles in 45, 40, and 35 degrees made it very attractive to Bell engineers to replicate.

Initially, the Bell engineers, similar to the intel provided by Voigt, concluded that the P.1011 was inferior to the American technology.

However, Woods would push his way to develop an aircraft based on P.1011. The design team at Bell proposed to build a bigger aircraft, which would be able to sweep its wings during flight. This was a major improvement from the P.1011, which could sweep its wings only before takeoff.

Read More: Lockheed D-21 – A UFO Spotter’s Dream

The Air Force HQ and NACA had heavily invested in experimental models such as the X-4, X-2, and XF-92A, and were interested in having a variable sweep angle aircraft for research purposes. That is why, in February 1949, Air Force approved the project.

Two years later, in June 1951, Bell delivered the first aircraft at Edwards Air Force Base in California, named X-5 with the serial number 50-1838.

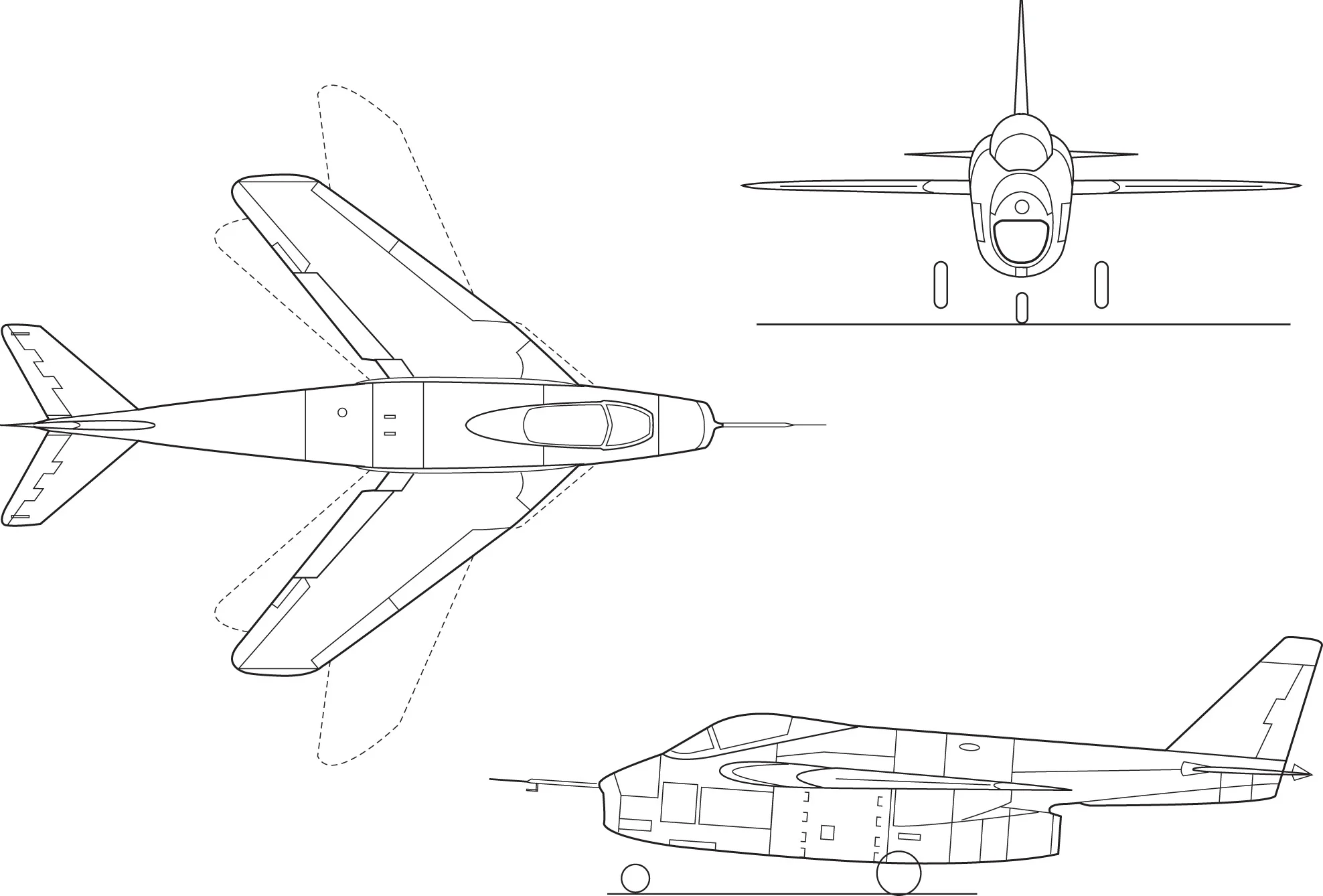

The design of the aircraft was very similar to the P.1011, consisting of many of P.1011’s original design features like the nose-mounted in-take and a boom-mounted tail. But the X-5 was able to pivot its wings from 20 to 60-degree mid-air.

Nevertheless, this improvement came with its own challenges, since the variable wing sweep required a complex mechanism to adapt to the change in the aircraft’s center of gravity and pressure.

As the wings swept back, the whole wing system would move further to the front to compensate for the sweeping back and balance the weight distribution of the plane.

The sweeping back from 20 to 60 degrees could be achieved in 20 seconds if no complications occurred. However, the aircraft was not considered safe to land at an angle greater than 40 degrees.

Operational History

The aircraft’s operational history began with a chain of testing, starting with Bell pilots, followed by Air Force, and finally the NACA. The plane had 20 flights conducted by Bell pilots. The first flight took place on June 20th and the plane was piloted by Skip Zieger. It took 8 flights before the engineers decided to test the wing sweeping mechanism.

When the mechanism proved to be operational, Bell passed the plane to the Air Force for their series of testing. At the Air Force, the plane was added 6 more flights to its tally, before turning it over to the NACA, in January 1952.

The intended destination for the plane was the NACA, where the aircraft went through extensive testing, by numerous pilots. These testing were much more demanding than the testing for Convair XF-92 and the Douglas X-3.

The research and testing were focused on the stability and control of the aircraft. Nevertheless, the plane went through research in other areas as well, throughout the 3 and a half years of operations at the NACA. During its time there the pilots of NACA used the X-5 for drag studies conducted with the plane having to fly behind F-80 and B-29 and B-47.

The aircraft was also tested for vertical tail loads in maneuvers and effects of dynamic pressure on buffeting among other tests.

The numerous pilots who flew the plane managed to identify numerous problems with the plane during the 133 flights with the first prototype (50-1838) and around 70 more flights with the second prototype (50-1839).

Read More: Curtiss XP-55 Ascender – The Flawed Fighter

The most significant problem with the plane was the ability to maneuver it during a spin. Pilots consistently reported that once the X-5 started to spin it was extremely difficult to recover. NACA pilot Joe Walker reported that in 1952 while flying at 36,000 feet, he lost control of the plane as it started spinning, and it took him 18,000 feet to regain control of the plane from the spin.

Similarly, NACA pilot A. Scott Crossfield managed to recover from a dangerous spin and come out without a scratch. But, the U.S. Air Force Pilot, Maj. Raymond Popson was not as fortunate as the two NACA pilots. He also entered a spin while piloting the X-5 (50-1839), and did not manage to regain control of the plane in time.

He crashed in October 1953 resulting in his death. The plane had its wings swept at 60 degrees before it crashed.

Crossfield best elaborated on other faults of the aircraft, which might have led to its complex spin problem. He described that the aircraft had a low-slung engine and problems with misalignment of the drag, principal, and thrust axis.

NACA pilot, Stanley Butchart further reported problems with speed brakes. Since the aircraft’s speed brakes were positioned in the front of the aircraft, the aircraft would get a nose-down pitch whenever the speed brakes opened, which was very unsafe by any standard.

Considering that the planes were intended for research and testing and that there were only two units of this aircraft, pilots would choose to avoid dangerous maneuvers, rather than complain about the aircraft.

In October 1955, this plane had its last flight, which will go into history not only as the career-ending event of this legendary experimental aircraft but also because the last man to fly it was a young Neil A. Armstrong.

He completed the last flight of Bell X-5, 14 years before he gained the status of the first man to walk on the moon. The plane retired immediately after it displayed problems with a gear door.

Bell would also propose to replace X-5’s original engines with the Wright J65 or Westinghouse J45 engines, which would increase its speed, however, these plans never took off.

In March 1958, the aircraft was sent to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. It is still on display at the Research & Development Hangar.

Conclusion

Overall, the X-5 validated the theoretical predictions that variable wing sweeping would reduce drag and improve the general performance of the aircraft in the air.

Nevertheless, the complex mechanism of moving the wings forwards as they were increasing the sweep angle, was considered impractical. This led the NACA engineers to come up with the solution of moving the pivot points outside of the aircraft’s fuselage.

Read More: Designed at Area 51 – The Secret Boeing Bird of Prey

The spin problems were attributed to design issues rather than the variable-sweep wings, as reported by Crossfield and Butchart.

That is why the improved variable-sweep wing concept was implemented in many aircraft after the 60s by both sides of the Iron Curtain.

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Specifications

- Crew: 1

- Length: 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m)

- Wingspan:

- Unsweept:30 ft 6 in (9.30 m)

- Swept wingspan: 20 ft 9 in (6.32 m) swept at 60° sweep

- Height: 12 ft 0 in (3.66 m)

- Wing area: 175 sq ft (16.3 m2)

- Empty weight: 6,350 lb (2,880 kg)

- Maximum takeoff weight: 9,980 lb (4,536 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Allison J35-A-17A turbojet engine, 4,900 lbf (22 kN) thrust at sea level

- Maximum speed: 705 mph (1,135 km/h, 613 kn)

- Range: 750 mi (1,210 km, 650 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 49,900 ft (15,200 m)