More than any other contemporary air service, the German Luftwaffe during World War Two explored the outer limits of aircraft design. They didn’t have much choice. Facing the combined industrial might of the United States and the Soviet Union, Germany simply could not produce conventional aircraft in sufficient numbers to effectively fight the Allied air forces.

Instead, they looked to new technology to give their aircraft a performance edge that would overcome the deficit in numbers. The Luftwaffe introduced not just the first jet fighter into operational service (the Me 262) but also the first and only rocket interceptor ever used in combat (the Me 163 Komet). They also explored radical point-defence fighters that would have used VTOL capability, though none were completed before the end of the war.

But perhaps no Luftwaffe project of World War Two was more futuristic than that which led to a jet-powered flying wing fighter/bomber. Even more surprising, this aircraft was designed and created by two brothers with little formal engineering training. This is the story of the Horten brothers, their flying wings and the astounding Ho 229.

Contents

Origin

The Treaty of Versailles that ended World War One essentially banned Germany from developing military aircraft and having an air force. Because of this, many German aircraft designers turned either to civil aircraft or to the design of gliders (which were permitted under the treaty).

Read More: Convair FISH & KINGFISH – The Stealth Parasites

In the 1920s and 1930s, German gliders became some of the most advanced in the world and German pilots held most of the top gliding records.

Two German brothers, Reimar and Walter Horten, became enthusiastic members of a gliding club in the late 1920s and spent time in the heart of the German gliding scene, the Wasserkuppe mountain.

However, the brothers weren’t content simply to fly the gliders they found there. They also began to design and build their own radical new designs, though neither had any formal aviation or engineering training.

Inspired by the designs of another German designer, Alexander Lippisch, who produced several tail-less delta gliders, the Horten brothers explored the concept of a flying wing design.

Their first gliders were simply vast wings with no conventional tail and in several early models, the pilot lay prone to improve streamlining. These first gliders weren’t easy to fly, but they did have very good performance – one of the advantages of the flying wing approach is the very low parasitic drag created by the airframe.

That is ideal in a glider, but it wasn’t long before the Horten brothers began to wonder if this approach might not also provide performance advantages in a powered aircraft.

Due to their lack of technical qualifications, the Hortens were largely ignored by most large German aircraft companies, being regarded as little more than enthusiastic amateurs with some rather odd ideas of aircraft design. However, both were members of the Nazi Party and that gave them distinct advantages in making the right contacts after the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933.

The first powered Horten aircraft, the Horten Va, began construction in 1936. The Hortens were supported in this build by Dynamit AG who were experimenting with new synthetic materials.

This aircraft was once again a flying wing design, with a mostly wooden structure covered in an early plastic, Trolitax. The front centre section of the wing was glazed with another synthetic material, transparent Cellon.

Read More: Kaman K-MAX Helicopter – Function over Form

In the cockpit, the two crew members sat side-by-side at the leading edge of the wing. Power was provided by a pair of tiny Hirth HM.60-R engines driving a pair of two-bladed propellors in the trailing edge of the wing. On its maiden flight, with Reimar and Walter at the controls, the Va crashed immediately after take-off. Fortunately, neither brother was seriously injured and soon after another prototype, the Vb was completed.

This version used a more conventional wood and metal construction and the novel wingtip controls used by the Va were abandoned in favour of conventional elevons.

The Hirth engines were salvaged from the Va and reused, though in the Vb they were mounted further forward and drove propellors through extended shafts. This improved weight distribution (thought to be the cause of the crash of the Va) and the Vb made a number of short flights in 1937 and 1938.

However, there was little official interest in the flying wing concept. The Luftwaffe was taking delivery of a new fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, which was as good or better than any other single-seat fighter then in service anywhere in the world and there seemed little need to further explore such a radical concept.

Reimar and Walter Horten abandoned their design work, the Vb was left to decay and the brothers joined the Luftwaffe and trained as fighter pilots.

Walter Horten flew the Bf 109 during the Battle of Britain before becoming the Technical Department Head of Luftwaffe-Inspektion 3 (Luftwaffe Inspectorate for Fighters). In 1941, he was able to persuade his superiors that it was time the re-visit the flying wing concept.

A new detachment was created in Minden to build a new version of the Horten V. In charge of this detachment was Reimar Horten, who had also qualified as a fighter pilot before being posted to the Luftwaffe gliding section.

Did The Horten Flying Wing Ever Fly?

Yes, the Horten flying wing, specifically the Horten Ho 229, did indeed fly. Back in 1943, this all-wing and jet-propelled aircraft promised remarkable performance.

The head of the German air force, Hermann Göring, recognized the possibilities of a new aircraft. He gave half a million Reich Marks to the inventors for constructing and trying out various models.

Despite facing many technical issues and the sole powered model meeting an accident after a few trials, it still stands out as one of the most unique fighter planes examined during the Second World War.

The Ho 229

Under the direction of the new detachment, two Horten-powered flying wing aircraft were completed at Minden. The Vc was an improved version of the Vb, though the only example was lost after a crash in the summer of 1943.

The VII was originally envisaged as a flying test bed for the Argus pulse-jet engine, but slow progress on that project meant that it was instead powered by two Argus AS-b-C engines driving a pair of two-bladed pusher propellors mounted on extension shafts.

In-flight tests, the VII performed satisfactorily, though its tiny engines meant that it was painfully slow. There was some discussion of using this aircraft as a trainer for fighter pilots, but in truth, no one could see a military role for the VII.

That might have been the end of the Horten flying wing story but, it was shown to the Head of the Luftwaffe, Herman Goering. He was sufficiently impressed that he ordered 20 examples to be built (though none would be completed before the end of the war).

He also provided funds and encouragement for the Horten brothers to explore something much more radical – combining their flying wing design with the then-new jet engines to create a fighter/bomber capable of meeting the “3×1000” requirement raised in 1943.

Read More: ATLAS-1 – The Space Mission to Understand the Atmosphere

This called for an aircraft capable of carrying 1,000kg of bombs over a range of 1,000 kilometres and at a speed of 1,000km/h.

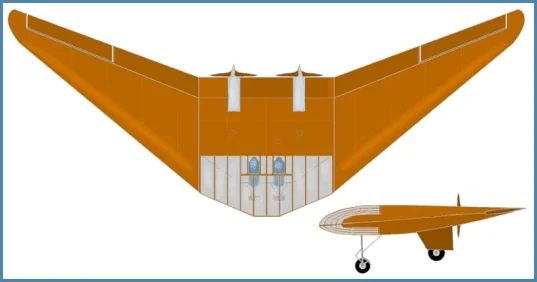

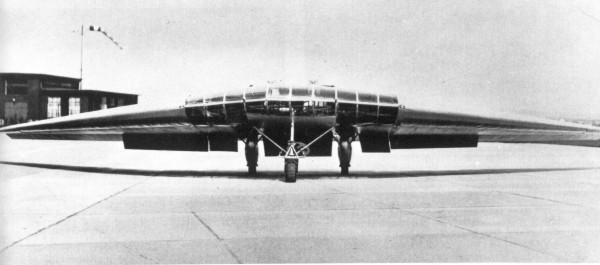

The Horten HIX (which was given the RLM designation Ho 229) was to be a single-seat, flying wing powered by two turbojet engines. Initial design work suggested that it was the only aircraft potentially capable of meeting the 3×1000 requirement and that it might also be able to operate at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet. An order was immediately placed for the construction of three prototypes.

The new aircraft was to be a flying wing with a conventional single-seat cockpit in the front of the fuselage centre section. In addition to its ability to carry up to 1,000 kg of bombs, RLM also demanded that it be armed with a pair of 30mm cannons.

If the performance predicted by the Hortens proved to be accurate, it was believed that this aircraft might also make a formidable fighter.

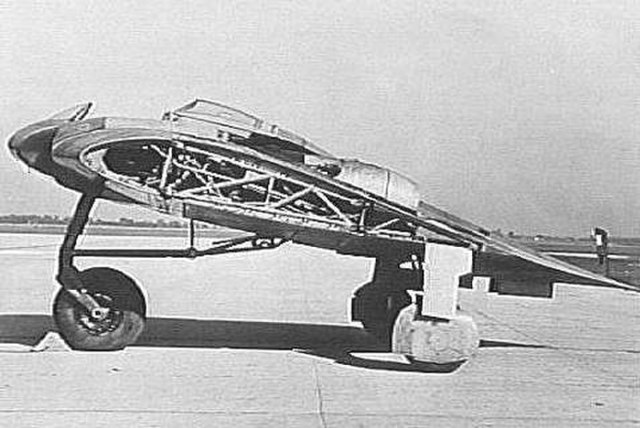

The centre section was made from welded steel tubing while the wing spars were wood. The whole aircraft was covered in a skin formed from thin sheets of plywood. To speed up construction, many preexisting components were re-used.

The tricycle undercarriage was created by using the tailwheel from a Heinkel He 177 bomber as the nosewheel and undercarriage legs from a Bf 109 fighter for the main gear. The pilot was provided with an early ejector seat and would wear a pressure suit – this would enable flight at high altitudes without the complexity of a pressurised pilot compartment.

The engines originally envisaged were BMW 003 turbojets, but delays in the development of this engine led to a switch to the Jumo 004 turbojet also used in the Messerschmitt Me 262 fighter and Arado Ar 234 bomber. The Jumo engines were larger than the BMW which involved the redesign of the centre section of the Ho 229.

An unpowered version, the Ho 229 V1, was completed and successfully flown, proving that at least the new design was capable of flight. On February 2nd 1945, the powered Ho 229 V2 was finally rolled out for its first flight.

It was piloted by Leutnant Erwin Ziller and the first flight, lasting just 30 minutes, seemed to go well. The following day, Zimmer flew the Ho 229 again but as he approached for landing, he inadvertently deployed the drogue parachute, causing a very heavy landing that damaged the aircraft. This was repaired and on 18th February, Ziller took the Ho 229 on its third flight.

After 45 minutes in the air, he approached the field but lost control and the aircraft crashed into the ground, completely destroying the prototype and killing the pilot.

Despite this, work on the Ho 229 continued. Gothaer Waggonfabrik was commissioned to build a third prototype and to prepare this aircraft for mass production. This project received priority when it was included in the Jäger-Notprogramm (Emergency Fighter Program), introduced in the summer of 1944 to accelerate the production of advanced-technology weapons.

However, no example of what was designated the Go 229 was ever completed before the war ended. The incomplete V3 prototype was captured by US forces when they occupied the Gotha Works and is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

Even before the sole flying, powered Ho 229 prototype was lost in February 1945, the Horten brothers had already begun work on an even more ambitious design, the Horten HXVIII, an intercontinental flying wing bomber powered by four or six jet engines that might have been capable of bombing targets in North America. Fortunately the war came to an end before this new project moved beyond the design stage.

Conclusion

The Ho 229 was a notable example of the Luftwaffe’s adoption of advanced technology in World War Two. It was the first turbojet-powered flying wing ever created and the few test flights completed seemed to suggest that it would have had a satisfactory performance.

However, like many Luftwaffe Wunderwaffe (Wonder Weapons) it was too little and too late to make any difference to the war.

One issue that is often raised in relation to this aircraft is whether it might have been “stealthy,” that is, difficult or impossible to detect on the radar? There is simply no evidence to suggest that this was considered during the design process, though the Ho 229’s wooden skin and a lack of sharp edges would probably have given it an unusually small radar cross-section. In that sense, the Ho 229 can certainly be seen as a forerunner of the F-117 Stealth Fighter or even of the flying wing B2 Stealth Bomber.

Read More: Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird – The Plane Designed to Leak

After the War, Reimar Horten remained in Germany and became an officer in the post-war Luftwaffe. Walter emigrated to Argentina where he continued to design tail-less aircraft. One of those was the FMA I.Ae 38 Naranjero (Orange Tree), an extraordinary flying wing powered by four piston engines and designed as a high speed cargo aircraft that would be used to rapidly transport oranges to Buenos Aires.

The only prototype made a few short flights in the early 1960s before the project was abandoned, effectively bringing to an end the story of Horten flying wings.

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.