The Hawker Typhoon “Tiffy,” was a flawed fighter that became an outstanding close-support aircraft. Even before the first Hawker Hurricane fighters were delivered to RAF squadrons, Sydney Camm, Hawker’s Chief Designer, was already working on the design of the Hurricane’s replacement, an even more advanced British fighter.

The new aircraft was to have at least 20% more performance than the Hurricane and it was the most powerful and heaviest fighter aircraft design anywhere in the world at the time.

The outcome would be the Hawker Typhoon which entered RAF service in September 1941. However, the new aircraft proved to have some fundamental flaws. During the first nine months of service it was estimated that on average, in each mission involving Typhoon squadrons, one aircraft was lost not to combat but to structural or engine failures.

Read More: Me 262 Schwalbe – Troubled Development

The Typhoon gained a terrible reputation amongst its pilots and it came close to being withdrawn from service altogether. Instead, its problems were addressed and it finally found its true role not as a fighter, but as an outstanding close-support aircraft.

Contents

Origin

The Hawker Hurricane proved to be a reliable and effective fighter, particularly when used as a bomber interceptor during the Battle of Britain. But despite its modern appearance, the Hurricane wasn’t part of the latest generation of combat aircraft exemplified by the Supermarine Spitfire and the German Bf 109.

Read More: Lockheed A-12 Oxcart – The Blackbird’s Older Brother

In terms of construction, the Hurricane was an interim design that drew from the biplane fighters of the 1920s and 1930s.

Although the basic structure of the Hurricane fuselage was made from a lattice of mechanically joined metal tubes rigged with internal steel wires to provide rigidity, the outer structure was constructed of plywood formers covered in doped Irish linen.

This was the same approach used in RAF inter-war biplane fighters and it led to the Hurricane initially being identified within Hawker as the “Fury Monoplane” (the Hawker Fury was a biplane fighter used by the RAF in the 1930s).

This design approach had advantages: it was very robust and capable of absorbing significant combat damage and it was familiar to the RAF riggers and fitters who had previously worked on biplanes.

But it also had notable disadvantages: it was complex to produce, requiring a range of skills in working with metal, wood and linen, and it simply wasn’t as strong as the latest monocoque all-metal designs where an outer stressed skin of thin metal gave great rigidity.

Sydney Camm was well aware of the limitations of the Hurricane and in 1937, he began sketching out designs for a replacement featuring an all-metal, stressed skin fuselage with heavier armament and a more powerful engine.

Read More: Avro 691 Lancastrian – The Very First Jet Airliner

In January 1938, the British Air Ministry issued a new specification, F.18/37, for a new single-seat fighter that would be even faster and more heavily armed than the Spitfires and Hurricanes only then beginning to enter service.

This specification envisaged the use of one of two powerful new aero-engines then under development: the Rolls-Royce Vulture “X” type and the Napier Sabre “H” type.

Design

Using the work already done by Camm, the design of the new fighter proceeded quickly. It was to be armed with no less than 12, .303 machine guns mounted in thick wings with a span of 40 feet.

The forward fuselage would use a tubular metal design, but the wings and rear fuselage would use a riveted, stressed-skin, monocoque approach, the first time that this had been used on any Hawker aircraft.

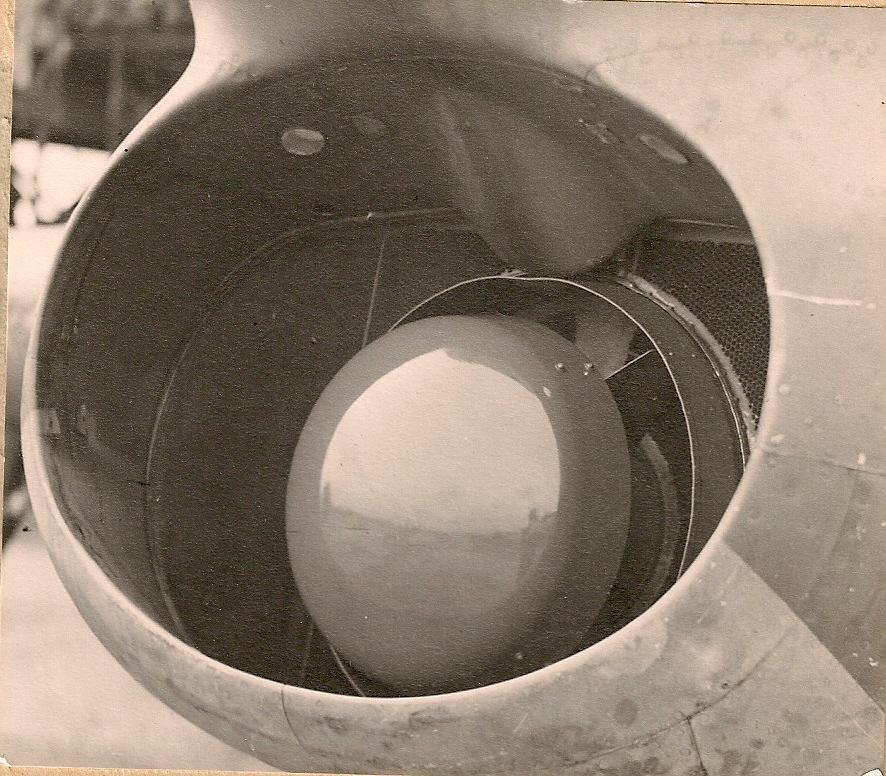

Two distinct versions were envisaged: the Tornado, powered by the Rolls-Royce engine and the Typhoon, powered by the Napier engine. Both were similar in appearance, though the Tornado featured a ventral radiator while the Typhoon was provided with a large chin radiator.

The Tornado prototype was the first to fly in October 1939. However, although it was fast at over 400mph in level flight, it suffered from serious issues with what is now known as compressibility effects in a dive, a sudden increase in drag caused by the creation of shock waves on the surface of the wing as an aircraft approached transonic flight.

This wasn’t well understood in 1939, and it was suspected that the large ventral radiator was the cause of the problem.

This was redesigned as a chin radiator, similar to that seen on the Typhoon, but only a single production version of the Hawker Tornado was ever built. The main problem with the Tornado was its Rolls-Royce engine.

The Merlin engine was desperately needed in 1940 to keep existing British fighters flying, and it was decided that Rolls-Royce would focus on the production and development of the Merlin rather than spend time developing the new Vulture.

Thus the Napier-engine Typhoon was selected as the version on which Hawker would concentrate, and the first prototype of that aircraft flew in February 1940.

The Napier Sabre was a complex engine, water cooled and with its 24 cylinders arranged in an H pattern. However, it was also massively powerful: during tests in 1938, it was found to be able to produce well over 2,000hp (the early Merlin engine fitted to the Hurricane produced a little over 1,100hp).

In early testing in the Typhoon, the Napier Sabre performed well, producing more than enough power and proving reliable. However, these early engines were hand-produced in-house by highly skilled Napier workers. What no one guessed was that this advanced engine would prove extremely troublesome when it was mass-produced by less skilled workers.

The armament originally envisaged for the Typhoon, 12 machine guns, would be retained and a new wing was also designed that could be armed with four Hispano 20mm cannons.

This would enter production as the Typhoon Ib and this would be the most common version of the Typhoon. However, early flight testing identified some serious problems.

The heavy engine was mounted almost level with the wing leading edge, and this was found to cause serious buffeting problems during some phases of flight – in one test flight this had become so serious that part of the stressed skin of the wing peeled off and the test pilot was fortunate to be able to return safely.

Read More: Kaman K-MAX Helicopter – Function over Form

The aircraft’s overall performance was also disappointing. While it was excellent at low altitudes, it had relatively poor climb performance and it was notably less effective at higher altitudes.

However, the appearance of a new German fighter, the Fw 190, in 1941 was causing problems for RAF squadrons equipped with the Spitfire Mk V.

Although issues remained with the new aircraft, two squadrons began to receive the first Typhoons in September 1941. It was left to RAF pilots to discover the many faults that still remained.

Typhoon Operational Use

From the very beginning of its RAF service, the Typhoon suffered from two fundamental problems. One was its Sabre engine. The mass-produced version of this engine proved to have a range of problems from badly machined valve sleeves to poor-quality castings.

It also proved very difficult to start in cold weather: mechanics often had to start the engine every two hours during the night to ensure that it would start on cold mornings.

The Typhoon also suffered from recurring structural failures. These led to the unexplained loss of several aircraft. Some were probably as a result of compressibility problems in high-speed dives, but the tail section of the aircraft had also been seen to break off in high-speed flight, often killing the pilot.

There were also problems with fumes from leaks in the complex exhaust system reaching the cockpit and it is believed that some unexplained losses may have been caused by the pilot suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning.

It was obvious that the Typhoon had potential, but it was equally obvious that it simply wasn’t ready for combat use in 1941 or for most of 1942. Non-combat losses in Typhoon squadrons became so serious that the RAF considered withdrawing the type from service.

Perhaps nothing exemplifies the potential and issues with the Typhoon better than a brief action during the Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee) in August 1942. Three RAF squadrons equipped with Typhoons took part in the air support operation for this action.

At one point, a flight of Typhoons dived on a flight of Fw 190s. The Typhoon’s awesome firepower ensured that three of the German aircraft were badly damaged, but two of the Typhoons suffered a structural failure of their tail sections during the dive and both crashed.

In the same month, a Typhoon being flown by a Hawker test pilot and carrying out a low-level, high-speed flight test crashed then the tail section broke off in flight, killing the pilot.

Hawker was able to recover the aircraft and discover that the failure had been caused when the elevator mass balance had torn away during high-speed flight.

This caused flutter in the tail which was so severe that the entire tail section broke off the aircraft. This led to the redesign of the whole tail section and the elevator mass balance which finally addressed this problem.

Gradually, the problems with the Sabre engine were also addressed. Machined nitride steel valve sleeves reduced failures in this area and improved quality control lessened reliability problems due to faulty castings in mass-produced engines.

Napier was considering fitting the Sabre engine with a supercharger to overcome the Typhoon’s climb and high altitude problems when the Air Ministry decided that instead, the Typhoon would be retained, but it would be switched to a different role.

The new Spitfire IX had proven to be an effective fighter and so instead, the Typhoon would become a dedicated close-support aircraft where its lack of high-altitude performance wouldn’t be a problem.

In this new role, the Typhoon proved to be outstanding. By the end of 1942, when structural issues and reliability issues with the Sabre engines had been addressed, Typhoons began to be fitted with bomb racks. With its massive power, the Typhoon could carry up to two, 1,000lb bombs or a load of eight unguided 3-inch rockets.

Combined with the firepower of four 20mm cannons in the Mk Ib version, the Typhoon became devastating when used in low-level attacks against enemy ground targets including trains, AFVs and convoys of vehicles. It could also still achieve close to 400mph at a low level even when loaded with ordnance, which made it difficult for enemy gunners to hit.

During the campaign in Normandy in June/July 1944, the RAF had 26 squadrons equipped with Typhoon Ibs and these aircraft destroyed over 130 German AFVs in the course of four weeks.

Over 3,000 Typhoons were produced in total and this type remained in RAF service until the end of the war. Hawker worked on an upgraded version, the Typhoon II, but this was so different that it became the greatly improved Tempest, introduced in early 1944.

Read More: “Taffy” Holden – The Aircraft Engineer Who Accidently Took Off

Conclusion

The Hawker Typhoon was designed as a fighter, but limited climb ability and high altitude performance made it relatively ineffective in this role. It had powerful armament, but early issues with the reliability of its Sabre engine and structural failures made it more lethal to its RAF pilots than to the Luftwaffe. The simple truth was that the Typhoon was introduced too early and before its development was complete.

The Typhoon was almost dropped entirely but gradually, its problems were addressed until, in late 1942, it was switched to a role for which it had never been intended, close support at low altitude. In this new role, it proved superlative and it finally gained the affectionate nickname by which it would become known for the rest of the war: Tiffy.

It took a very long time and cost the lives of many RAF pilots, but the Tiffy finally became one of the most effective and feared of all British combat aircraft during World War Two.

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Specifications

- Crew: One

- Length: 31 ft 11.5 in (9.741 m)

- Wingspan: 41 ft 7 in (12.67 m)

- Height: 15 ft 4 in (4.67 m)

- Empty weight: 8,840 lb (4,010 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 13,250 lb (6,010 kg) with two 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs

- Powerplant: 1 × Napier Sabre IIA, IIB or IIC H-24 liquid-cooled sleeve-valve piston engine, 2,180 hp (1,630 kW)

- Maximum speed: 412 mph (663 km/h, 358 kn) at 19,000 ft (5,800 m)

- Range: 510 mi (820 km, 440 nmi) with two 500 lb (230 kg) bombs

- Service ceiling: 35,200 ft (10,700 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,740 ft/min (13.9 m/s) F.S supercharger at 3,700 rpm and 14,300 ft (4,400 m)