During wartime, genuine innovation is surprisingly rare. And this was the case with the XB-42. Rather than creating something entirely new, it’s less risky, quicker and uses fewer resources just to make a bigger, better, or faster version of what you already have.

Occasionally a talented designer will be allowed to sit down in front of a blank sheet of paper, forget what has come before and allow their imagination to run wild.

Contents

Inception

Edward F. Burton, Chief of Engineering at the Douglas Aircraft Company, was given a simple but daunting brief: design a twin-engine tactical bomber capable of achieving 400mph and carrying a bomb-load of 2,000 lbs over a range of 2,000 miles.

To put this in context, the Douglas A-20G Havoc then in large-scale production, could reach a maximum speed of 317mph with a range of under 1,000 miles carrying a bomb load of 4,000lbs.

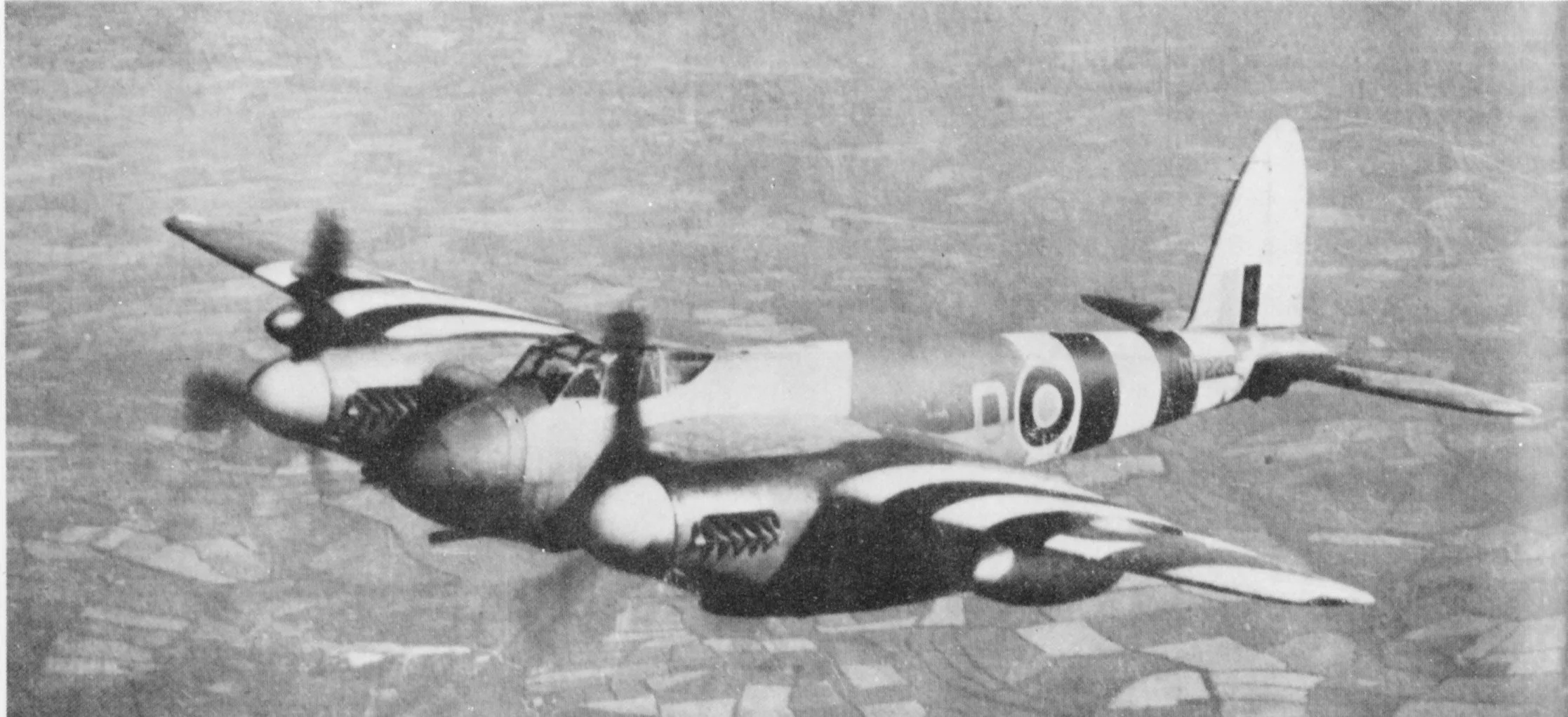

Even the British de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito, revered as one of the fastest light bombers of World War Two, could barely reach 400mph and had a range of under 1,300 miles with a bomb load of up to 4,000lbs.

To meet the brief, it was clear that a radical design would be needed. The planned top speed would require plenty of power. Almost every other multi-engine military and civilian aircraft of the period used engines mounted in pods in or under the wings.

But engine pods also create drag. Adding more engines gives more power, but also adds drag. To achieve the power and range required, Burton wanted to keep the wings of the new design clean and free from drag-inducing engine pods.

XB-42

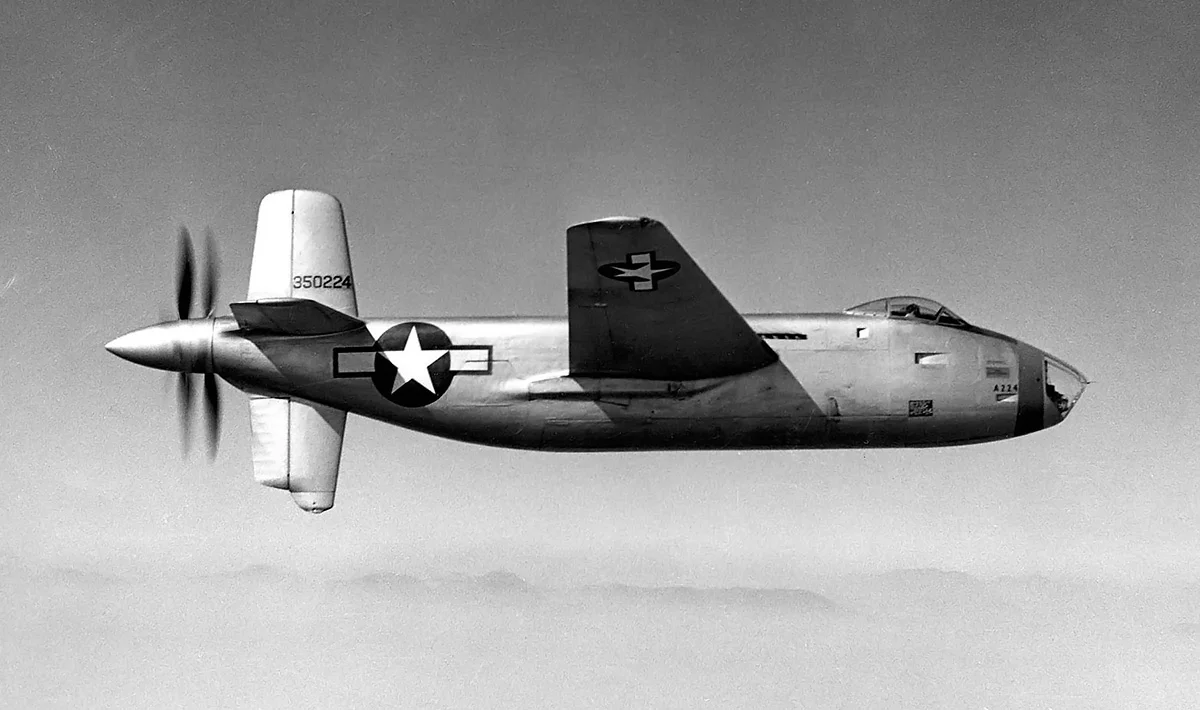

In 1943 the resulting aircraft was an all-metal, mid-wing monoplane with a sleek, streamlined fuselage and laminar-flow wings featuring double-slotted flaps. The two engines were located side-by-side inside the fuselage, driving a pair of contra-rotating pusher propellors in the tail.

To keep the wings as thin as possible, the main wheels of the tricycle undercarriage rotated through 180˚ during retraction so that they could be housed in the fuselage.

The Allison V-1710 engines were located close to the aircraft’s center of gravity and transferred power via a system of shafts to a reduction gearbox in the tail. This provided power to two large contra-rotating, three-blade Curtiss Electric propellers.

The engines could be operated independently and the aircraft was designed to be flyable on one engine. Cooling and intake air to the engines was provided through narrow slots in the inboard leading edge of each wing. The exhausts ran through openings in the rear of the wings and vents on top of the fuselage.

To prevent damage to the propellors through ground strike during take-off and landing, the ventral fin was extended below the fuselage and capped with a pneumatic bumper.

The crew of three (pilot, co-pilot and bombardier) were housed in the front of the nose. In the initial design, the pilot and co-pilot had separate bubble canopies and the bombardier sat in the glazed nose section.

Obviously, baling out of any aircraft can be very hazardous, but especially with one using a pusher propeller configuration, so explosive charges were included in the rear section. These could be used to separate the gearbox and propellers from the fuselage to allow safe egress in flight.

Armament

Defensive armament comprised four .50-cal machine guns, housed under protective covers in the trailing edges of the wings. Once operated, each pair of machine guns would emerge from behind a snap-action cover and could be angled through 35˚ vertically and 50˚ horizontally.

These guns were remotely controlled from the co-pilot’s position: the seat could be rotated through 180˚ to face the gun control panel at the rear of the cockpit.

The bomb bay featured two snap-action doors and could carry up to 8,000 lbs of bombs, or a single 10,0000lb bomb if the doors were left slightly open. The bay was also designed to be long enough to carry two standard US Navy torpedoes if required.

Attacker or Bomber?

The design work for this aircraft was undertaken independently by Douglas without a specification from the US Army Air Force (USAAF). In early 1943, Douglas confidently predicted that what was then called the Douglas Model 459 would have a range of over 5,000 miles and a top speed of 470mph.

In May 1943, the design was submitted to the USAAF for evaluation. They were sufficiently impressed that in June 1943 an order was placed for two prototypes and a single static test aircraft. Initially, the USAAF wanted this to be developed as an attack aircraft, with a mix of cannon and machine guns in a solid nose.

For this reason, the prototypes were initially given the USAAF designation XA-42. However, this soon changed and both prototypes were completed as tactical bombers and given the designation XB-42.

Flight Performance

A mock-up was built and approved in September 1943 and the first XB-42 prototype was completed in early May 1944. It first flew on 6th May and a second prototype (with slightly more powerful engines) flew for the first time on 1st August.

Early flight testing revealed several issues with the XB-42. Most notably, the ventral fin was only 9 inches from the runway with the aircraft fully loaded. This made conventional rotation impossible: instead, the aircraft had to be allowed to gain sufficient speed that it would lift off almost flat. This required a very long take-off run of over 6,000 feet and a very careful approach and landing.

When in the air, there were other issues. Vibration from the rear propellors was very noticeable. This was just about acceptable when the aircraft was clean, but with the bomb bay doors open or when the gear and flaps were extended, it became so severe that some test crews felt that it was dangerous.

At lower speeds, the aircraft had a tendency to Dutch Roll, a very uncomfortable combination of uncommanded yaw and roll. The twin bubble canopies were not popular and were felt to restrict communication between pilot and co-pilot.

However, the most serious problem was performance, or rather, the lack of it. Both prototypes were heavier than expected, which reduced performance well below what was expected. The maximum airspeed of the first prototype was found to be around 370mph.

That was good, but it wasn’t close to what had been expected and it certainly wasn’t fast enough to make the XB-42, as Douglas had claimed, so fast that it would be able to avoid interception by most contemporary fighters.

A number of modifications were undertaken on the second prototype to reduce weight, including the fitment of hollow-blade propellers, but this was found to make the vibration problem even worse.

The vertical stabilizer was increased in size in order address the Dutch Roll issue. This helped, but didn’t completely solve the problem. A single conventional canopy replaced the twin bubble canopies. There were cooling problems with the engines too, and the inlets in the wing leading edges were made larger, but this also led to a slight decrease in speed.

The modified second XB-42 was handed over to the USAAF in early 1945 for evaluation. During this time, it was given the unofficial name by which it would become known: the Mixmaster.

This was due to its large propellers which resembled a blender. On December 8th, it was used to set a new record for a coast-to-coast flight across America, flying from Long Beach in California to Bolling Field in Washington, D.C. in a little over 5¼ hours.

A USAAF press release triumphantly noted that this involved an average speed of 433mph. That sounded good, but what wasn’t mentioned was that the flight benefitted from strong tailwinds throughout, and the true airspeed was actually around 375mph. Fast, but not fast enough to make the other issues with XB-42 irrelevant.

Failure?

Just eight days later, the same XB-42 was lost in a landing accident at Bolling Field. While on approach, the landing gear failed to extend properly. While trying to solve this problem, the crew noticed that one of the engines was overheating badly. It was shut down and the second engine was brought to full power.

It too began to overheat and the decision was taken to abandon the aircraft. Only when the co-pilot and bombardier had baled out did the pilot notice that he had forgotten to jettison the gearbox and propellers.

He did so before leaving the aircraft himself. Remarkably, all three men survived but the XB-42 was completely destroyed.

However, by that time, the war was over and military aviation had already switched to looking to jet engines to provide increased performance. The first XB-42 prototype was modified with the addition of two Westinghouse J30 jet engines in pods under the wings to become the XB-42A. It was faster in this configuration, reaching a top speed of 480mph.

However, it still had the inherent problems that had afflicted the original and it wasn’t as fast as the new all-jet designs that were beginning to appear when it first flew in May 1947, including the XB-43 Jetmaster developed by Douglas. No further development work on the XB-42 was carried out.

The last XB-42 was decommissioned by the US Air Force in 1949 and presented to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. It was never placed on display and unfortunately, at some point, the wings were lost (which begs the question: how can you lose something as large as a pair of wings for a tactical bomber!).

In 2010 the fuselage was transferred to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio where it is currently awaiting restoration and display.

Douglas Aircraft didn’t abandon the pusher concept after the XB-42. The Douglas DC-8 Skybus airliner was based on the XB-42 design, with two of the same Allison V-1710 engines in the fuselage powering a pair of contra-rotating propellers in the tail.

However, the potential performance increases over conventional airliners were negated by the complexity, cost and handling issues associated with this configuration and this aircraft never went beyond the design stage. The Martin 202A and Convair 240 were both much less risky designs that were chosen instead.

In 1947, Douglas did produce a single prototype of the Cloudster II, a five-seat light aircraft using the same configuration. However, this flew only twice: the vibration problems that affected the XB-42 were even worse on this small aircraft.

However, what finally killed this design was cost: this was a complex design and to be commercially viable, Douglas estimated that it would have to be sold for more than twice the price of other similar light aircraft of the period.

The XB-42 was a bold and completely different design for a tactical bomber, but it also graphically illustrates the inherent risks of innovation. The performance that the design seemed to offer was never achieved in reality and problems with vibration, uncoordinated controls, engine cooling and a very long take-off run were never satisfactorily addressed.

A willingness to innovate can lead to notable advances, but sometimes it just creates more problems than it solves.

Another Article From Us: Blackburn/Hawker Siddeley Buccaneer – Carrier-Based Attacker

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Specifications

- Crew: three (pilot, co-pilot, bombardier)

- Length: 53 ft 8 in (16.36 m)

- Wingspan: 70 ft 6 in (21.49 m)

- Height: 18 ft 10 in (5.74 m)

- Empty weight: 20,888 lb (9,475 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 35,702 lb (16,194 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Allison V-1710-125 liquid-cooled V-12, 1,800 hp (1,300 kW) each

- Maximum speed: 410 mph (660 km/h, 360 kn) at 23,440 feet (7,140 m)

- Range: 1,800 mi (2,900 km, 1,600 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 29,400 ft (9,000 m)

- Guns: 6 × .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns – two in twin rear-firing turrets and two fixed forward-firing

- Bombs: 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) in internal bay