During the interwar period Italian manufacturer Savoia-Marchetti was inspired to create a new aircraft that could act as a torpedo bomber – the S.55. What they envisioned would lie quietly in wait on the surface of the sea for enemy ships to come into range.

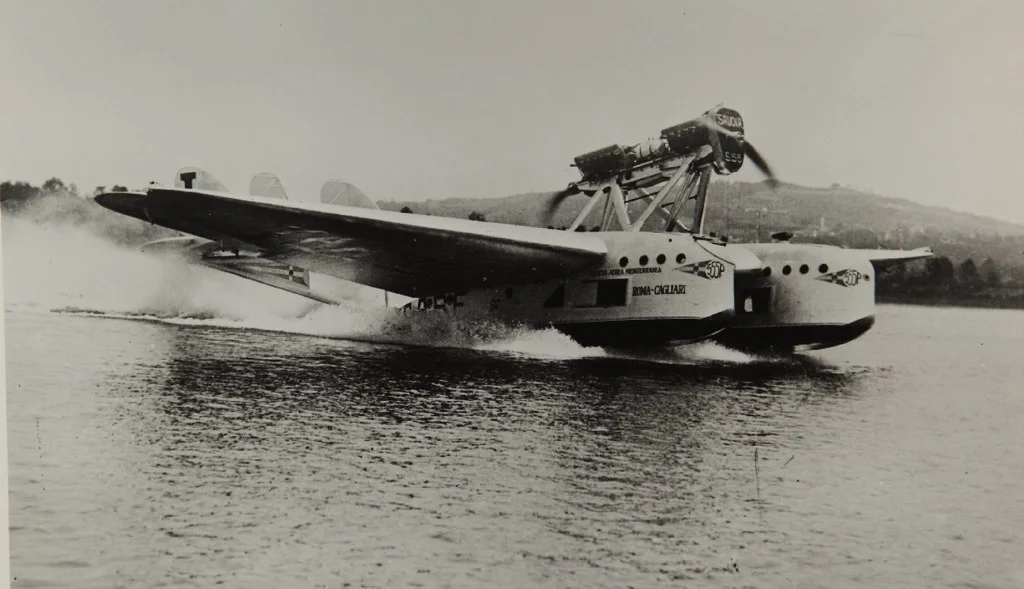

Debuting in 1924 the Italians were initially unsure about the new flying boat, which although earmarked for a role on the battlefield, would in the end go on to cement its reputation in a completely different arena.

Contents

The S.55

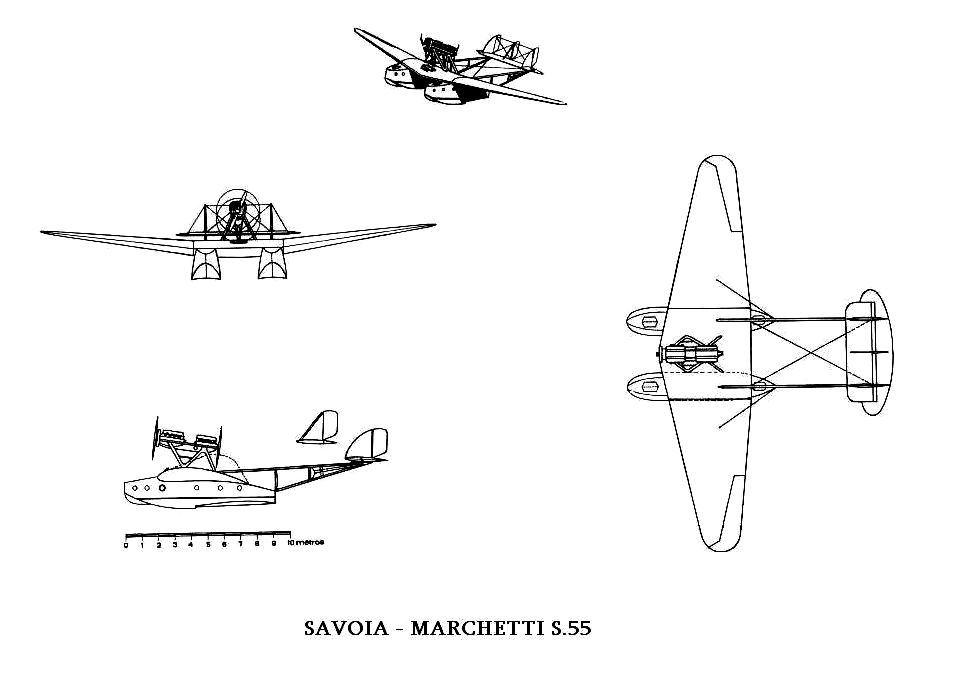

The Savoia-Marchetti S.55 was 16 meters in length, and 5 meters in height, and had a take-off weight of 8,260 kilograms and an empty weight of 3,700 kilograms.

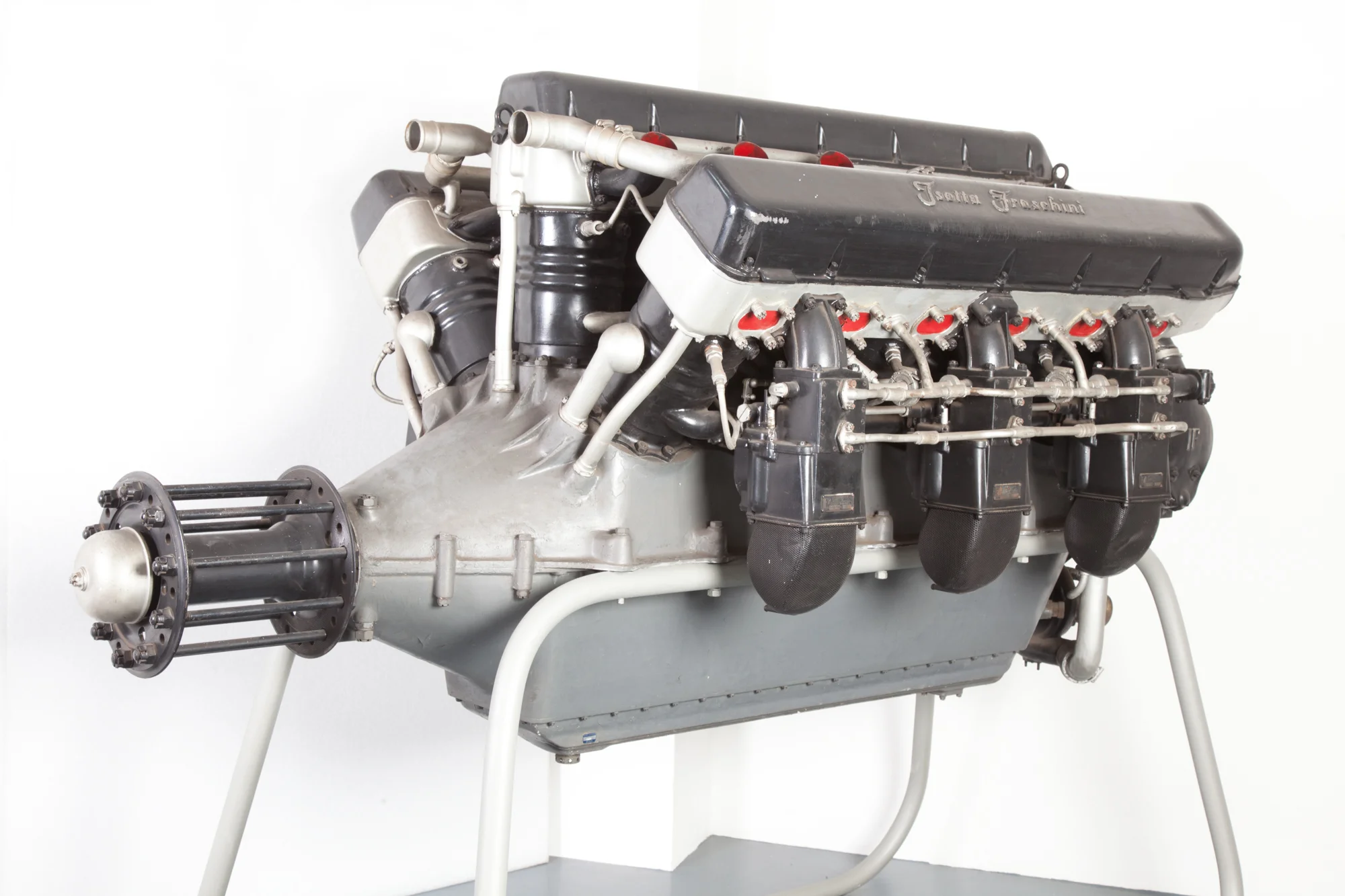

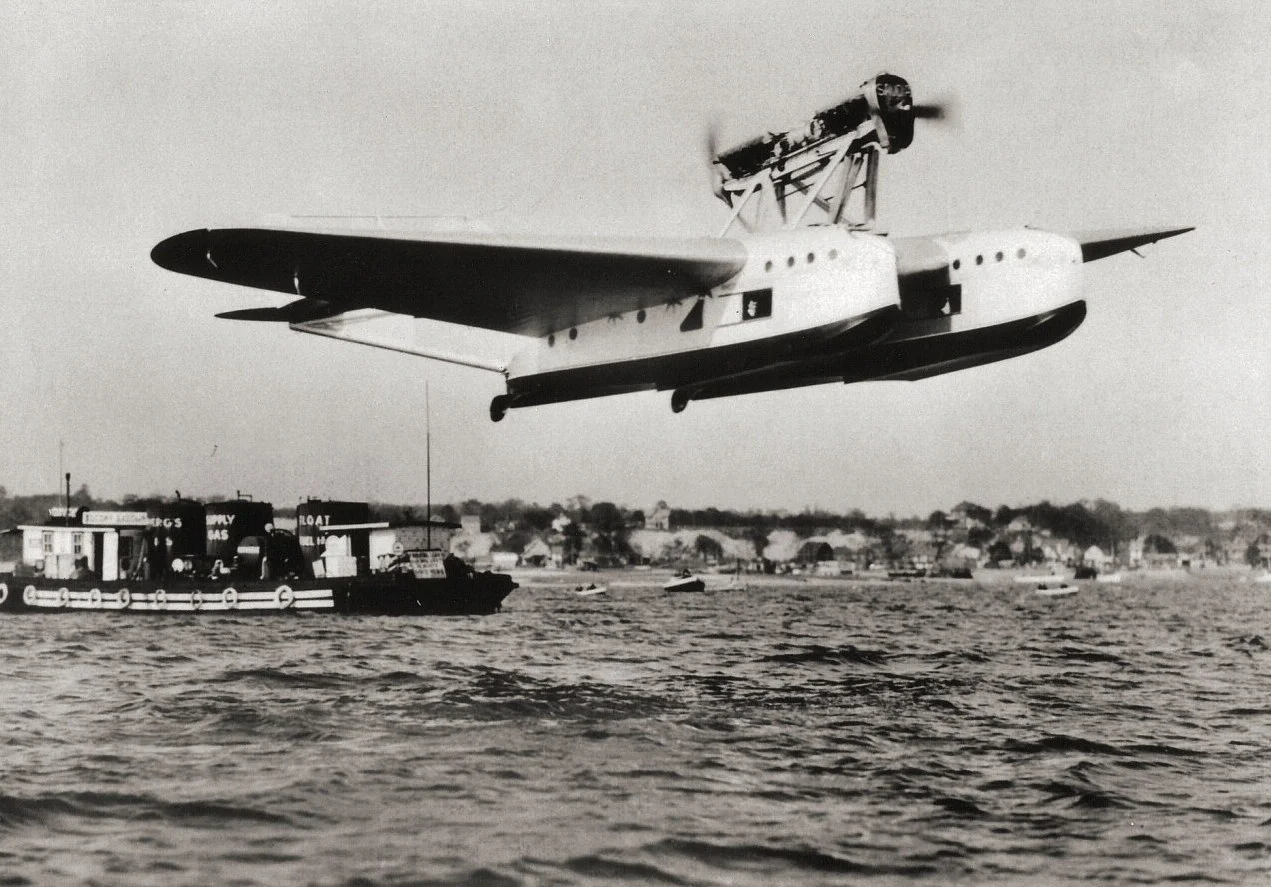

It was launched through the skies with twin 400 horsepower Lorraine Dietrich power plants or dual 656-kilowatt Isotta-Fraschini Asso 750R engines mounted on top of the wings on a system of M-struts and cooled by a radiator located at the nose of the engine container, achieving a top speed of 173 miles per hour, a cruise speed of 145 miles per hour, a maximum range of 2,796 miles, and an altitude ceiling of 16,400 feet, which it could climb to in 60 minutes.

Read More: Messerschmitt Bf 110 – Harmless by Day, Lethal by Night

A cantilever shoulder-wing monoplane that could operate from water, the S.55 was primarily made out of wood because chief designer Alessandro Marchetti calculated that metal would cause the cost to increase by as much as 3 times.

It was manned by a crew of 5 or 6 comprising two pilots, who sat in neighboring cockpits situated on the leading edge of the centre-wing section.

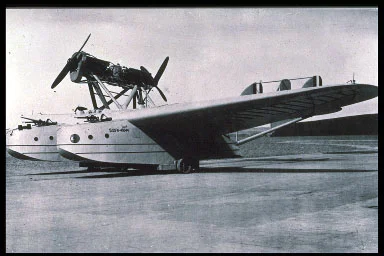

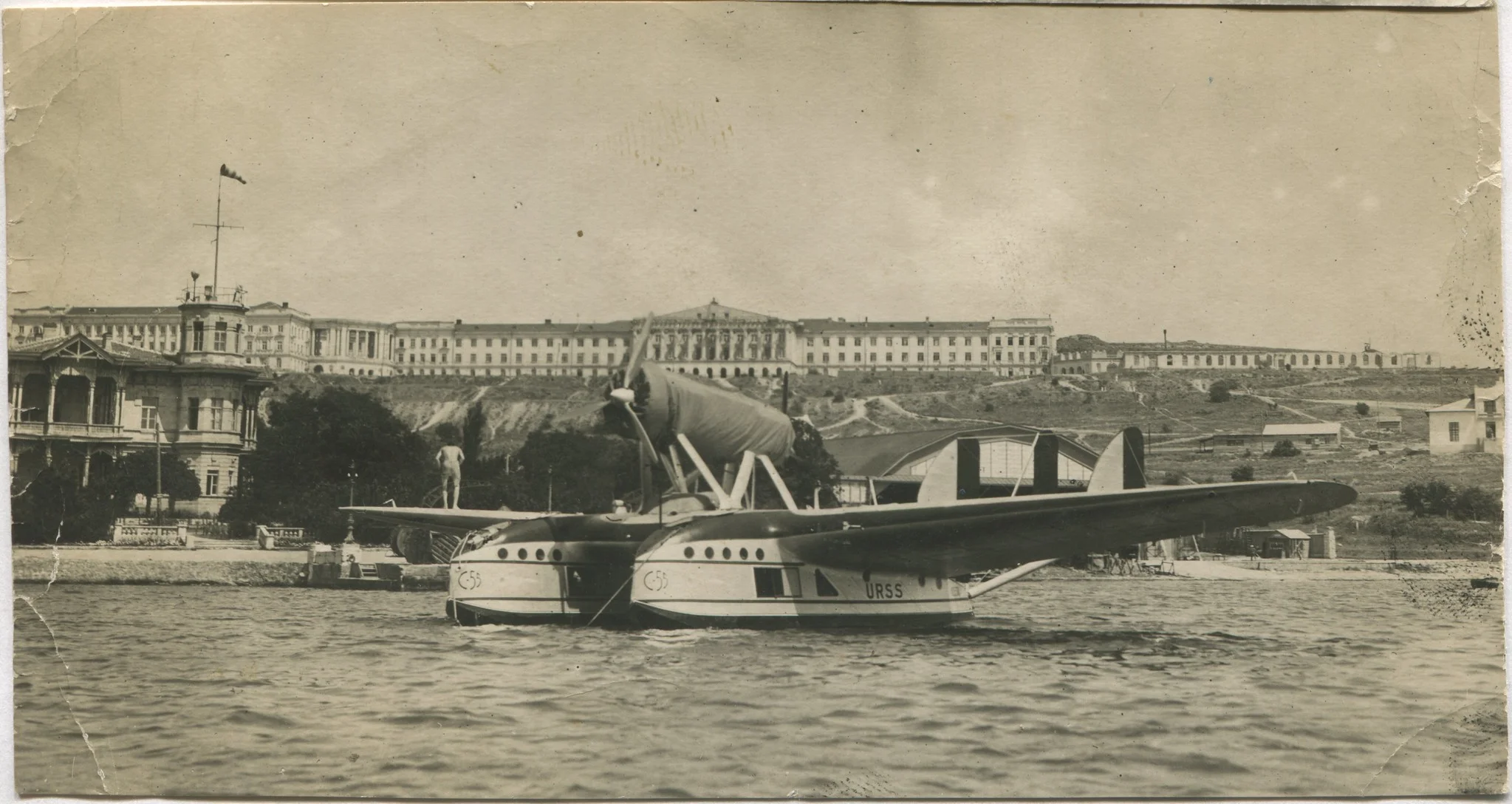

Among some of its most groundbreaking features were twin concave-shaped hulls in the style of a catamaran, which if necessary could accommodate 12 passengers, and a slightly inclined engine angled downwards at 8 degrees which reduced hydrodynamic drag when it took off from the water.

In fact, the hull of the S.55 was considered so pioneering that it was evaluated by NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) in 1938 for possible use in future US seaplanes and compared with their own Model 35 prototype, where its resistant characteristics at all speeds were considered excellent by assessors.

The wings, which had a span of 24 meters and an area of 93 meters squared, had a pronounced dihedral angle at their outer section and a leading edge that was swept back about 15 degrees. In addition to having dual V-tails, there were 3 triangular-shaped vertical wings mounted on top of a horizontal stabilizing surface of 97 square feet, with balance rudders attached to the trailing edges. If necessary, the S.55 could be dismantled for transport very easily, for the wings were composed of 3 detachable sections while the hulls and the tail could all be easily removed.

Unlike the later S.55X edition, the original was conceived as a torpedo bomber and was fitted with an 800-kilogram weapon suspended from the central-wing section that could be armed with torpedoes, bombs, or mine-laying equipment, with an 8-foot gap purposefully spaced between the hulls to act as a safety mechanism. Covering fire was provided by twin 7.7 mm machine guns located on each engine nacelle, with gunner’s cockpits in the stern of each hull.

Operational History

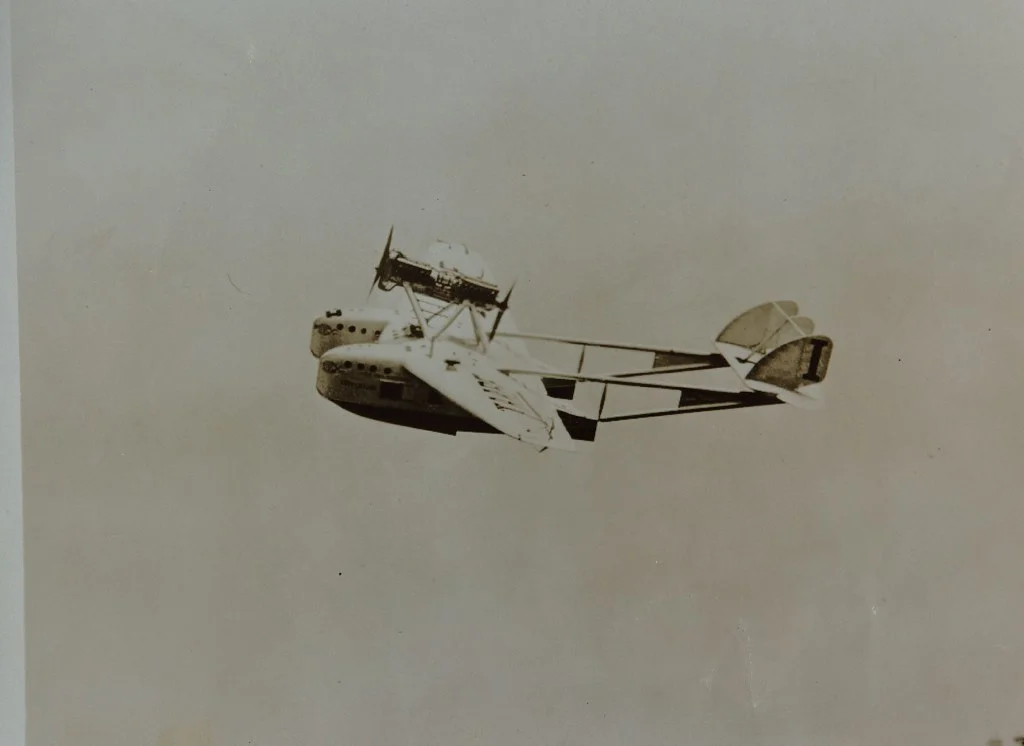

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Savoia-Marchetti S.55 was lauded as the poster child of Italian aviation and was the main star of a variety of stunts intended to champion Italian engineering prowess.

The Savoia-Marchetti S.55 became most renowned for its feats of endurance, such as in 1926, when it set speed records in 14 categories, including for endurance and altitude, and also in 1927, when Italian aviation aficionado De Pinedo-Del Prete flew the ’Santa Maria’ 42,000 kilometers in a journey involving a two-way crossing of the Atlantic Sea from Sardinia to Buenos Aires.

In another well-publicized trip in the same year, Brazilian pilot João Ribeiro de Barros in the ‘Jahú’ would mark the first-ever transatlantic flight of an aviator from the Western Hemisphere after taking off from Sao Paulo and landing in Italy.

The S.55 further proved a reliable endurance craft in 1928 when 8 units traveled 2,800 kilometers as part of the first mass Mediterranean cruise and again in 1929 when 37 of them were called up to participate in the second mass Mediterranean cruise, covering a distance of 4,800 kilometers.

Building on these foundations, the S.55 was selected by Italian general Italo Balbo to fly in mass formation across the Atlantic, the first of which occurred in December 1930 when a fleet of S.55s traveled 10,400 kilometers between Italy and Brazil.

Balbo commanded 12 more similar missions, a string of assignments that was somewhat marred by an unfortunate incident in January 1931, involving the Savoia-Marchetti S.55 registered as I-DONA, which after setting off from Guinea Bissau westwards started to encounter technical issues 1,000 kilometers from the Brazilian coast sufficiently serious enough to warrant an emergency landing in the ocean.

Read More: Douglas A-20/DB-7 Havoc – Upward Guns?

Although the aircraft broke up and sunk to the bottom of the sea, all 4 crew members would live to tell the tale, having been rescued by a near convoy of Italian battleships, but Balbo organized his most ambitious flyover in 1933.

Christened the ‘Aerial Armada’ by the world press, in the opening stage of the ‘Decennial Air Cruise’ celebrating 10 years of the Italian Air Force, 24 S.55s famously flew from Rome to Chicago via Iceland, Greenland, and Labrador Island, paying a visit to the Chicago 1933 Century of Progress Exposition, while on the return leg they passed through New York, the Azores, and Lisbon.

Despite being generally viewed as a triumph there were a handful of casualties. On July 1st, 1933 an S.55 following behind Balbo attempted to land at the harbor of Schellingwoude in Amsterdam, only to hit a nearby dam which killed crew member Sergeant Quintavalle, a tragedy that was mirrored towards the end of the tour on August 8th by the death of another serviceman, who lost his life after his S.55 hurtled into the ocean while trying to take off from Ponta Delgada in the Azores archipelago.

Discounting the mishaps, the flights were deemed a success to many at the time who believed the results illustrated that transatlantic travel could be performed safely and that a long-distance commercial airliner service could be a workable enterprise.

In fact, two civil aviation versions, the S.55C, and the S.55P were developed soon after, flying commercial routes over the Mediterranean for around a decade.

Although eclipsed by endurance achievements the S.55 was also deployed, seeing action in the Spanish Civil War bombing Republican ships and becoming the main unit of Italy’s maritime-bombing squadrons throughout the 1930s, 13 of which remained on call as reserves by 1939.

It also served as a military plane for the Brazilian Army in the 1930s where it was involved in two major accidents. The first occurred on September 3rd, 1931 when 2 S.55s on local assignment in Rio de Janeiro inexplicably lost control and collided with each other before plummeting into Guanabara Bay.

In equally uncertain circumstances less than a year later on April 26th, 1932, a government S.55 crashed on the runway while landing in the Bay of Salvador de Bahia, killing two passengers and the radio navigator but sparing the life of a Brazilian Minister of Transport and Public Works José Américo de Almeida, who survived with sustained injuries.

Replica

The last surviving example of the S.55 is the same one flown by João Ribeiro de Barros in 1928 and currently resides neglected in the TAM Museum in Sao Paulo, Brazil, which has closed down in recent times. The lack of exposure has spurred a new generation of aviation enthusiasts, technicians, and journalists, helped by ex-Savoia-Marchetti employees, to rebuild an entirely new S.55 from the ground up.

Read More: Fw 200 Condor – The Airliner that went to War

The Savoia Marchetti Historical Group, entrusted with safeguarding the history of Savoia-Marchetti for the public, has been working since 2015 to faithfully recreate this storied airplane in preparation for the centenary of the Italian Air Force and the S.55’s first flight in 2023, which will also commemorate the 90th anniversary of Italo Balbo’s 1933 mass flight across the Atlantic.

Coordinated by Filippo Meani, the society has painstakingly searched for surviving S.55 parts and leafed through 900 original assembly documents relating to the S.55 from the 14,000 Savoia-Marchetti technical documents under their care.

Taking great pains to conform to the manufacturing process outlined in the original blueprints, the model, although not flyable, is planned to be of the highest museum standard.

Despite being delayed by a pandemic great progress has been made and as of September 2022 the project, which began with the construction of the airframe at Volandia Museum, the second-largest aviation museum in Italy, is 75% complete and has already been fitted with twin hulls, tail-wings, the central section, and dummy engines. With the April 2023 deadline date looming, the Savoia Marchetti Historical Group next hopes to acquire two working Isotta Fraschini engines and to complete work on the central wing box.

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Specifications

- Crew: 2 pilots, 3-4 other crew members

- Length: 16.5 m (54 ft 2 in)

- Wingspan: 24 m (78 ft 9 in)

- Height: 5 m (16 ft 5 in)

- Empty weight: 5,750 kg (12,677 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 8,260 kg (18,210 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Isotta Fraschini Asso 500 V-12 water-cooled piston engines, 370 kW (500 hp) each mounted in tandem, plus one Garelli piston engine driving oil distribution placed between the two main engines

- Maximum speed: 205 km/h (127 mph, 111 kn)

- Range: 1,200 km (750 mi, 650 nmi) to 2,200 km (1,400 mi; 1,200 nmi)